This web-site is based on studies of Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica

(Dutch helleborine)

made by the author between 1985 and 2022. During that period, some papers on this taxon

have been published (KAPTEYN DEN BOUMEESTER, 1989, 2012 & 2018). The

text is occasionally adapted to new insights. Initially the taxon was considered to be a variety, but in the

beginning of 2018 the author grew convinced that a classification as subspecies would be more suitable (see text).

In the 4th version (Nov. 2022) the main page has become more compact and matters of secondary importance were

transferred to subpages.

Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica is the dune form of Epipactis

helleborine s.l.

This taxon was first described in 1949 by P. Vermeulen (VERMEULEN, 1949). He

subsequently described it in more detail in the Flora neerlandica (VERMEULEN 1958).

This variety is particularly associated with Dutch coastal dunes, but also occurs in the

Danish, German and Belgian coastal dunes (BUTTLER, 1986). It also grows at

Kenfig National Nature Reserve and other coastal dunes on the south coast of Wales.

Many specimens of this type were studied in the Dutch coastal dunes to establish if their

habitus and biotype ("habitat") were distinguished from inland forms of

E. helleborine, in particular "typical" woodland E. helleborine subsp.

helleborine. These studies established that subsp. neerlandica plants growing in coastal dunes in

association with Creeping Willow (Salix repens) are very similar to each other. They

also established that these plants are different from typical woodland inland forms

of subsp. helleborine. In the case of plants growing in other habitats, the situation is less

clear.

The taxon neerlandica was first described by VERMEULEN (1949) who named it as a variety, BUTTLER raised it to the rank of subspecies (in GREUTER, W. & RAUS, Th., 1986). DELFORGE, DEVILLERS-TERSCHUREN and DEVILLERS (1991) went further and promoted it to the rank of species.

On the herbarium sheet on which the holotype specimen of var. neerlandica is mounted, P. Vermeulen wrote by hand that "Hooge Duin en Daalscheweg near the Lonbar Petrilaan in Bloemendaal-Overveen" was the location of the type specimen (the "locus classicus"). However, a card labelled "Herbarium P. Vermeulen" gave this location as "Bloemendaal-Overveen Lage Duin en Daalscheweg near Lonbar Petrilaan. Dune edge. several specimens". Because the Lage Duinendaalseweg is further north, only the Hoge Duinendaalseweg could be meant. The actual site must be located on the southwest side of the Hoge Duinendaalseweg where old maps show a lot of open dunes. There were once shooting ranges there but Vermeulen does not mention them, and at that time there was apparently no fence along the road. Now the area is forested, protected by a fence and not open to the public. In 1997 it was declared a State Nature Reserve, along with several other sites in Overveen. Perhaps some neerlandica still grow there, although it is likely that any plants would be the intermediate form found in more shaded habitats (see below). The locus classicus is unlikely to have been on the northeast side of the Hoge Duinendaalseweg (estate Lindenheuvel) where old maps show a strip of wood along the road.

Vermeulen wrote: "The trip to Overveen was made to ascertain whether there would be E. dunensis plants (Godfery), but although these plants grew in the dunes they still had a well-developed rostellum, so that they must be considered to be latifolia as stated above. ..."

Apparently Vermeulen also contacted the English Epipactis specialist D.P. Young about his discovery because associated with the herbarium sheet there is a letter from Young to Vermeulen which reads:

|

E. latifolia var. neerlandica Verm. I agree that this is a var. or form of latifolia. A similar plant grows in Britain in the dunes at Kenfig (S. Wales), but is very rare. It is nothing to do with E. dunensis Godf. which has a more slender habit and much less copious roots, quite apart from different pollination mechanism. Oct. 1952. (signed: D.P. Young) (1st fig. lower right) |

| 1 | roots mostly springing from the rhizome in several levels, |

| 2 | stems at the bottom often purple, |

| 3 | leaves close together and short and firm, |

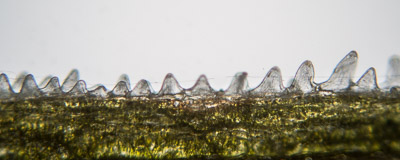

| 4 | leaf margin with papillae like isosceles triangles with the tips showing outwards (see 3.2), |

| 5 | raceme short to quite long, densely flowered, with densely hairy rachis, |

| 6 | bracts short (shorter than the typical subsp.), |

| 7 | flowers with purple colored petals and little or not at all wrinkled small bosses on the often purplish epichile, |

| 8 | ovary sometimes quite hairy. |

| 9 | a later flowering time than in the typical subsp. helleborine |

In addition to its characteristic habitus, according to VERMEULEN (1958), subsp. neerlandica is further characterised by the shape of the papillae on the leaf margins. As part of my studies this characteristic feature was also examined using specimens in the form of pieces of leaf margin about 3 cm long and 4 mm wide; this format has the following advantages: 1) the plant suffers no serious damage, 2), these small pieces are easier to dry than whole leaves, the outer margins of which often turn inwards, 3) they are large enough to write a number on it. The leaf specimens of dune plants were collected from sites in the Amsterdamse Waterleiding dunes (AWD) and also from other coastal dunes, while inland specimens were obtained from several localities in the Netherlands and Germany. According to VERMEULEN (1958: 101 and 104) the shape of the papillae on the leaf margins of typical subsp. helleborine is "scalene triangular with the tips bending towards the leaf tip". In the case of subsp. neerlandica the papillae are "as isosceles triangles with the tips pointing outwards". My studies established that the situation was rather more complicated. Thus, in some specimens of subsp. neerlandica that were in all other respects typical (see below), the tips of the papillae pointed forwards towards the leaf tip. In contrast, typical subsp. helleborine sometimes had papillae that did not point forwards towards the leaf tip, but instead pointed straight outwards. Based on my studies, the description of the papillae of the two varieties can be modified as follows: in subsp. helleborine the tips of the papillae usually point forwards and often some are hooked; also, these papillae, whether forward pointing or not, are clearly spaced from each other. In the case of subsp. neerlandica, whether growing in woodland or in the open, most papillae on the leaf margins point straight outwards; although forward pointing papillae also frequently occur, these are hardly ever hooked. In addition, the papillae of subsp. neerlandica are generally arranged more compactly, fitting together more tightly at the base and they are generally smaller than those of typical subsp. helleborine.

| leaf margin of Epipactis helleborine subsp. helleborine |

| leaf margin of Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica |

In the literature many characteristics are mentioned - some are useful, some not. >> A discussion on these characteristics can be found here

After discussing all propounded features some remain as useful. E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica is distinguished from subsp. helleborine as follows:

| 1 | leaves nearly always closer together at the base of the stem and firmer, |

| 2 | leaves usually erect and often channelled, |

| 3 | lower bracts usually shorter and usually not reflexed, |

| 4 | papillae different (see above 3.2), |

| 5 | inflorescence usually dense, |

| 6 | leaf margins quite often undulate, but not always; only as a supplementary feature, |

| 7 | stem usually with short, dense hair, |

| 8 | flowering time is later. |

The first five are the most important features.

It should be noticed, that the words "usually", "often" etc. are repeatedly used. Subsp.

neerlandica is just so close related to subsp. helleborine, that they have features

in common. A combination of several features is needed to distinguish between both taxa.

Only one feature is not sufficient.

|

| |||

All the E. helleborine plants I found in Creeping Willow vegetation showed these characteristics. These plants are therefore considered to be "typical" subsp. neerlandica. Similar plants are also sometimes found in pine and other woods on coastal dunes. However these woodland plants were often accompanied by a greater or smaller percentage of specimens that were difficult to identify. For example, in a strip of birch-wood on the eastern edge of the dunes at De Zilk, plants with typical subsp. neerlandica features were in the minority, although the others were not typical woodland subsp. helleborine. The flowering time in both coastal dune Creeping Willow vegetation and coastal woodland is later than inland, namely from early August to September, even October, peaking in mid to late August. The flower colour of these coastal plants is often yellow-green, with a red lip, but in some places there are also plants with reddish sepals and petals, reminiscent of Epipactis atrorubens.

|

| |||

While VERMEULEN (1958) named neerlandica as a variety of E. helleborine, BUTTLER (1986) raised it to the rank of subspecies. This new name was validly published (in: Greuter, W. & TH RAUS, 1986) but no reason for the change was given. BUTTLER also gave no clear reason for the change in a personal conversation. The fact that there are now reasons to classify the taxon as a subspecies is thus not Buttler's credit, but is based on later research by others.

To obtain the rank "subspecies", the neerlandica must meet the following requirements:

If one considers only neerlandica in coastal dune Creeping Willow vegetation, one could speak of a subspecies with its own characteristics and its own ecological niche. There is also largely a reproductive isolation. However, the occurrence of neerlandica in woodland seemed to indicate that it is not restricted to a specific ecological area. In addition, forms intermediate between subsp. neerlandica and subsp. helleborine also occur in woodland. Where do we go from here?

From all my observations between 1985 and now I will mention a few that are representative of the whole and that will lead, together with recent research by others, to a conclusion:

Two conclusions can be deduced from this:

Compared with typical subsp. neerlandica, intermediate forms growing in wooded areas of coastal dunes may have broader leaves, the leaves may spread out more, the papillae can point forward towards the leaf tip and can be longer; however, the leaves are not pendulous, the bracts are not very large and not pendulous and there are always at least some groups of characteristic closely arranged leaf margin papillae touching along the sides as well as at the base.

KUIPER, OOSTERMEIJER and GRAVENDEEL (2009) carried out experiments with cross-fertilization. Cross-fertilization resulted in 95% of viable seeds. In view of some overlap in flowering period, is also possible that hybridization between helleborine s.str. and neerlandica occasionally occurs in nature. The mycorrhizal fungi species found in neerlandica, also appear to occur in helleborine s.str. In addition, herbarium specimens of both varieties were morphologically compared. The authors concluded that the length and position of the bracts were the only useful distinguishing features. They also concluded that these two varieties are genetically not completely separated.

The claim that recent research (SCHIEBOLD, BIDARTONDO, KARASCH, GRAVENDEEL & GEBAUER, 2017) would prove that both taxa have their own specific fungi, can in fact not be deduced from this investigation. Only a very limited amount of plants and sites was investigated.

An investigation on a larger scale (50 plants of each taxon) by JACQUEMYN, DE KORT, VANDEN BROECK, & BRYS (2018) indicates, however, that the two taxa can be clearly distinguished both morphologically and genetically.

Morphologically, the average values of a large number of characteristics are compared. Of course, there are many individual plants that do not display those average values, but then a distinction based on the above described combination of characteristics is usually sufficient to distinguish subsp. neerlandica. Genetically, both taxa are also clearly different, with the diversity within subsp. neerlandica considerably smaller then that within subsp. helleborine.

Only the difference in the found mycorrhizal fungi is not convincing, given the large distance between the sites of both taxa. In their publication Jacquemyn et al. do not comment on the status; they call the taxa 'dune and forest ecotypes'.

Together with the already found morphological differences and ecological characteristics, the genetic differences and reproductive barriers found by JACQUEMYN et al. (2018), convinced me that there are sufficient differences to be able to speak of an ecological subspecies.

Shortly after I came to my conclusion I was informed, that R. Bateman, on the basis of his own research, also came to the conclusion that neerlandica should be considered as an ecological subspecies. During a conference at the end of March 2018 in Paris, in an informal talk between R. Bateman and H. Jacquemyn, it became also clear that they agreed about the status of neerlandica as a subspecies. In the meantime an elaborate article was published: SRAMKÓ, PAUN, BRANDRUD, LACZKÓ, MOLNÁR EN BATEMAN (2019). The studied samples of Dutch neerlandica were collected near Overveen in the company of G. SRAMKÓ (28 July 2015).

BATEMAN (2020) confirms my conclusions based on field observations by referring to more elaborate research on DNA data.

It now seems evident that subsp. helleborine evolved to colonise open, dry coastal habitats, probably in a very gradual manner. In the course of time the differences between dune and inland form grew and possibly they are still growing.

|  |

The occurrence of intermediate forms in shaded places could be explained as follows: On the one hand, there is so much genetic overlap between subsp. neerlandica and subsp. helleborine that, in shaded places, subsp. neerlandica can still develop morphological characteristics favourable to that habitat, in particular, a greater leaf surface, flatter leaves and a taller growth. However, in other respects these plants remain morphologically distinct from subsp. helleborine, in particular, as regards the leaf papillae and bracts. On the other hand, the adaptation to Creeping Willow vegetation habitats in open, dry coastal dunes requires such a high level of adaptation that subsp. helleborine cannot easily survive there. It is therefore concluded that many intermediate plants in the coastal dunes are forms of subsp. neerlandica and that subsp. helleborine is rarely represented there, if at all.

Following my visit to Kenfig in 2009, the above matter was discussed by email with L. Lewis and Jürgen Reinhardt. We concluded that subsp. neerlandica appeared to be a form adapted to the special circumstances of its open coastal dune habitat; also, that plants exist which are morphologically intermediate between subsp. neerlandica and subsp. helleborine. Reinhardt also noted that parallel developments of taxa adapted to dry habitats occur within the E. helleborine complex, e.g. E. helleborine subsp. tremolsii (PAU) KLEIN, E. helleborine subsp. latina ROSSI & KLEIN or E. helleborine subsp. orbicularis (RICHTER) KLEIN.

A similar adaptation would explain of reports of neerlandica-like plants growing in

inland, non-dune habitats in, for example, in

Gloucestershire (UK), on Rügen (D) and near Aachen (D). The plants near Aachen

look very like subsp. neerlandica in habitus (see photos in FRANZ, 2008), but the

papillae on the leaf margins sent to me were indistinguishable from those of typical subsp.

helleborine. These plants grow in dry habitats, but not in Creeping Willow vegetation

in

coastal dunes. These plants from inland habitats therefore appear to be a local adaptation to

open, dry conditions.

The same adaptation would appear to explain similar plants which grow in open coastal

dunes close to pine wood in The Raven, Nature Reserve on the east coast of County

Wexford in Ireland (2015).

M.J. CLARK (2011) reported plants which looked like typical subsp. helleborine growing in shade in woodland on the dunes at Kenfig (l.c. Fig. 8). These adopted the habitus of neerlandica (l.c. Fig. 7) after the trees shading them were removed. Based on this observation, he concluded that neerlandica is not a genetically distinct taxon but simply an ecad [= ecotype] morphologically adapted to growing in an open dune habitat. However, consistent with my conclusions above, my explanation is that the plants growing among the trees were not subsp. helleborine but were instead subsp. neerlandica, adapted to the shade. They therefore changed to their characteristic subsp. neerlandica habitus when they subsequently grew in full light after the trees had been removed. In my opinion, this is supported by the photograph of the woodland plant before the clearance (l.c. Fig. 8). Thus, the leaves of this plant are flat, not pendulous, and the distance between the leaves is shorter than for a typical subsp. helleborine; in addition, although the inflorescence is quite lax, the bracts are relatively short and not pendulous.

As explained above, subsp. neerlandica is morphologically distinguished from E. helleborine s.str. [= subsp. helleborine]. The genetic separation between these two taxa seems to be proved now by JACQUEMIN et. al. (2018) and SRAMKÓ, PAUN, BRANDRUD, LACZKÓ, MOLNÁR and BATEMAN (2019). The dune form has its own ecological niche. Therefore it can be considered to be a subspecies. The fact that subsp. neerlandica can grow in shaded habitats albeit with a slightly different habitus, seems not to detract the above argumentation, all the more since after the removal of the shade the typical features appear again.

As a working concept (not as a new classification), one could revive the term "praespecies" by SUNDERMANN (1975). It must be stressed however, that neither Sundermann in his time nor this author would like to add a new category to the nomenclature, but the term praespecies is only used as a working concept which makes it clear that the taxon is involved in an evolutionary process.

Most of my studies of subsp. neerlandica were conducted in the Amsterdamse Waterleidingduinen (AWD), roughly the dunes between Zandvoort and Noordwijkerhout, and sometimes in areas north to it.

Subsp. neerlandica is mainly found in the following habitats:

|  |

The flowering time of subsp. neerlandica was already mentioned: from early August to September, even October, peaking in mid to late August. However, on October 2nd, 1988 some plants were found that had not yet opened yet. They were not found in full bloom until October 23. No pollination occurred in any of these October flowering plants. It was observed that self-pollination does not occur even after a long period, but that stigma and rostellum gradually discolour and desiccate, while the pollinia remain in the clinandrium. Finally, the non-pollinated flowers fall off. Many buds of late-flowering plants also fall off fairly quickly.

The only exception was in 1991 when a plant was found in which there was probably self-pollination.

|  |

Wasps were photographed visiting subsp. neerlandica flowers in 1986 and 1987, but were not captured for identification since studying their behaviour was given priority at the time. Identification of these wasps was subsequently attempted based on photographs but proved difficult. Therefore, from 1988 onwards specimens of wasps were caught for identification and stored.

On 28-8-1987, the behaviour of wasps was observed in a pine wood. After studying photographs of one of the wasps and comparing them with specimens collected later, it was identified as a male Dolichovespula saxonica or D. sylvestris. Three wasps visited some subsp. neerlandica growing in groups. The wasps were all very slow in their movements. They also experienced difficulty in flying to more distant plants, sometimes making "emergency landings" on the ground. This behaviour has also been observed by LØJTNANT (1974), who believed that the nectar contains a poisonous substance, making the "wild" behaviour of the wasps slower and quieter. This would lead to the pollination of more flowers on one plant and thus increase the chance of survival or proliferation of the species. This form of pollination is not strictly self-pollination (autogamy) because the pollination does not take place within a single flower, but from a genetic viewpoint it is, because the flowers of only one plant are involved. This form of pollination is called 'geitonogamy' (= neighbour pollination), as opposed to the full cross-pollination (allogamy) between flowers of different plants, which is then called 'xenogamy' (= fertilization by cross-pollination between flowers on different plants) (among others WIEFELSPÜTZ, 1970).

VÖTH (1982, p. 425) had a different explanation for this wasp behaviour, namely that the nectar sometimes ferments in periods of extremely hot weather producing alcohol which intoxicates the wasps. If that were the case, the phenomenon should presumably happen in more localities. Also the weather in August 1987 was not extremely hot. LØJTNANT's theory neither explains why the phenomenon was observed in 1987 and not in 1988.

MÜLLER (1988) examined the nectar of E. helleborine and found that the nectar often contained a lot of ethanol (alcohol), which may be formed from the sugars under certain circumstances with the aid of the bacteria and yeasts that are often also present in the nectar. This explains the occurrence of "intoxicated" wasps. Thus Vöth's explanation seems justified, except that bacteria and yeasts also play a role and "excessive heat" is no longer decisive, consistent with my field observations in 1987 and 1988.

|  |

All the wasps I identified as visitors to subsp. neerlandica were males. However, VÖTH (1982) also observed female worker wasps visiting E. helleborine at the sites he studied. His explanation was that the flowering period of E. helleborine s.l. is coordinated with the time when the wasps switch from eating other insects (in order to feed the larvae) to sweet substances. Also CHINERY (1973) wrote that when the male and young queen wasps have left the nest, the colonies fall into decline and the workers switch to sweet substances. MÜLLER (1988) confirmed Dolichovespula saxonica as an important pollinator of subsp. helleborine and that the flowering time of this subsp. coincided with the time when the size of the colonies of that wasp species was at its largest. In Germany this is mainly early August. Assuming that if Dolichovespula saxonica is also the main pollinator of the later flowering subsp. neerlandica on coastal dunes, it seems probable that the maximum size of wasp colonies in this habitat is later than inland.

>> Go to a page with more observations of pollinators |  |

*) Erratum in Liparis 18, pg. 44, 3rd line above the photos. The text reads:

“[de] bracteeën zijn erg groot”. This

should be: “[de] bracteeën zijn niet erg groot”.